Oxidation and Hot Corrosion

Comprehensive Educational Resource for High-Temperature Metal Degradation

← Back to Main Page

← Back to Main Page

← Back to Main Page

Protective Coating

Protective coatings are essential for enhancing the high-temperature oxidation and corrosion resistance of metals and alloys in aggressive environments. These coatings provide a barrier between the substrate material and the corrosive environment, extending component lifetimes and enabling operation at higher temperatures than would otherwise be possible.

1

Diffusion coatings

Diffusion coatings are formed by the diffusion of elements into the substrate surface, creating a protective layer that is metallurgically bonded to the base material. These coatings provide excellent adhesion and can significantly enhance oxidation resistance.

1.1. Aluminizing of nickel-base alloys

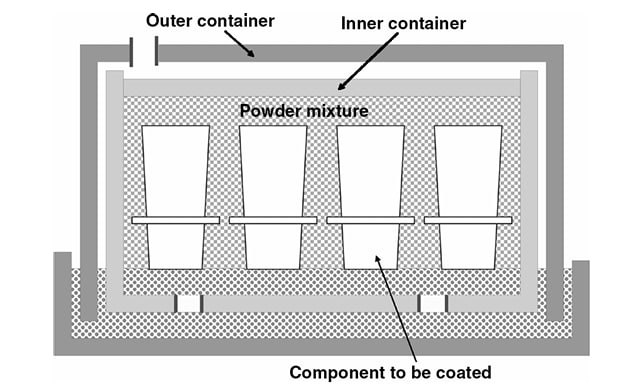

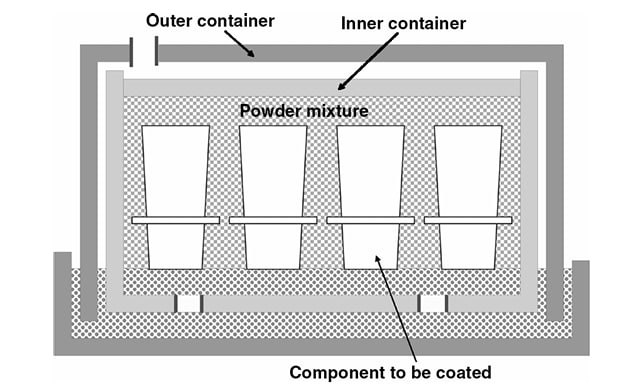

The most common method of aluminizing is pack cementation, which has been a commercially viable process for many years. This process, which is shown schematically in Figure 1, involves immersing the substrate in a mixture of powders. The mixture contains a powder source of Al, either Al metal or a suitable master alloy, a halide activator, and a filler, which is usually alumina and taken to be inert. A pack will usually contain 2–5% activator, 25% source and the rest filler. The purpose of the filler is to support the component and to provide a porous diffusion path for the gases generated by reaction between the source and activator.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of the pack cementation process for aluminizing.

Figure 2: Cross-sectional microstructure of an aluminide coating on a nickel-base superalloy.

1.2. Chromized coatings

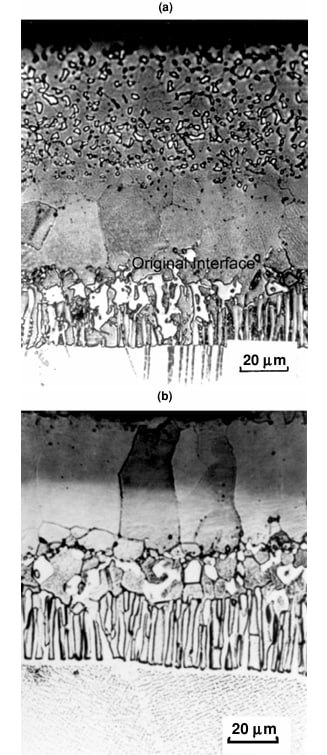

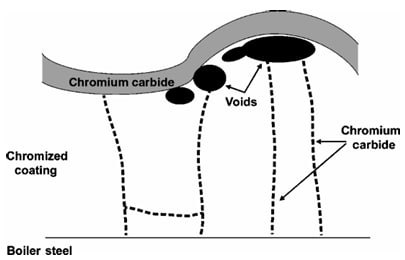

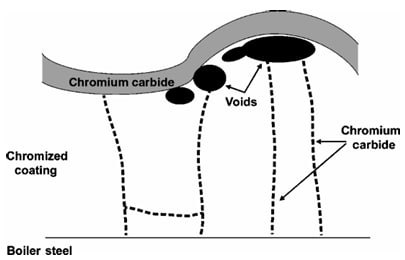

Chromized coatings can be formed by pack cementation in a manner similar to that described for aluminizing. Figure 1 presents a schematic cross-section of a typical chromized coating on a boiler steel. The coating consists of ferrite and Cr in solution and a Cr concentration gradient running from the surface to the coating–substrate interface. Carbon has diffused out from the steel and formed a chromium-carbide layer on the surface and chromium carbides have precipitated on grain boundaries in the coating. Voids are also evident below the outer carbide layer. When undesirable, the carbide layer and voids can be eliminated by choice of activator.

Figure 1: Schematic cross-section of a typical chromized coating on a boiler steel showing the chromium gradient and carbide formation.

1.3. Silicide coatings

The refractory-metal silicides have been used for many years to protect refractory metals from oxidation in very high-temperature, but short-duration applications. These coatings have been highly successful but their use in applications which require long-term stability has been limited by problems with accelerated oxidation and pesting, evaporation of SiO at low oxygen partial pressures, interdiffusion with the substrate, and cracking because of thermal-expansion mismatch between the coating and substrate. These factors have been reviewed in detail by Packer and Kircher and Courtright.

1.4. Other methods of forming diffusion coatings

Diffusion coatings can be formed by a number of methods which have not been described in detail. One such technique is slurry coating where the slurry is formed by using a volatile suspension medium that burns off upon heating. This can be accomplished by applying a slurry containing the activator and source metal on the surface of the substrate and heating to form a coating in a manner similar to pack cementation. Another variant involves using an activator-free slurry which will melt when the substrate is heated and then resolidify during interdiffusion with the substrate. Another simple technique is hot-dip coating in which the substrate is immersed in a liquid bath. The most common use of this process is for zinc coating (galvanizing) of steels but it is also extensively used to produce Al coatings on steels.

2

Overlay coatings

Overlay coatings are distinguished from the diffusion coatings in that the coating material is deposited onto the substrate in ways that only give enough interaction with the substrate to provide bonding of the coating. Since the substrate does not enter substantially into the coating formation, in principle, much greater coating composition flexibility is achievable with overlay coatings. Also, elements that are difficult to deposit into diffusion coatings, can be included in overlay coatings.

2.1. Physical vapour deposition (evaporation)

Physical vapour deposition is very versatile. It can be used to deposit metals, alloys, inorganic compounds, or mixtures of these and even some organic materials. The process consists of three principal steps:

- Synthesis of the material to be deposited.

- Transport of vapours from the source to the substrate.

- Condensation, film nucleation, and growth on the substrate.

Physical vapour deposition produces an overlay coating which has several important advantages over some other techniques:

- Composition flexibility.

- The substrate temperature can be varied over a wide range.

- High deposition rates.

- Excellent bonding.

- High-purity deposits.

- Excellent surface finish.

2.2. Spray techniques

2.2.1. Plasma spray processes

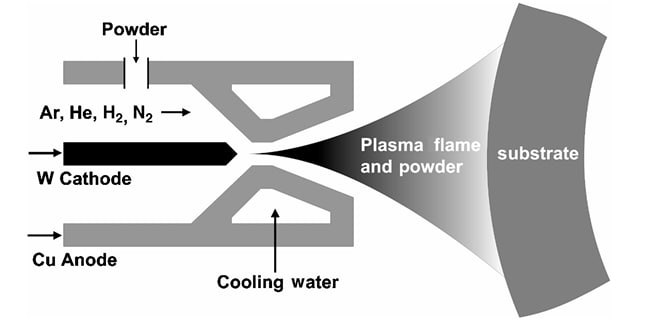

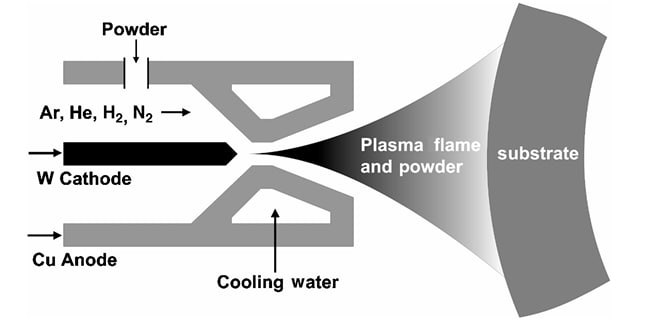

The plasma spray technique has been used for about 30 years. Figure 1 shows a simple schematic diagram of a plasma torch. Basically, a powder is fed into the plasma, which is used as a heater, and the molten product is sprayed onto the substrate to form just about any thickness. The coatings tend to be porous and of poor adhesion. The adhesion can be improved by increased surface roughness of the substrate, which can be produced by grit blasting.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of a plasma spray torch showing the powder feed, plasma generation, and coating formation process.

2.2.2. Detonation gun

Fixed amounts of powder are accelerated by successive explosions of an acetylene–oxygen mixture. This allows velocities of the order 750 m s−1 and temperatures of the order of 4000°C to be achieved leading to deposits of excellent bond strength but with some porosity.

2.2.3. Flame spraying

Flame spraying has been used mainly for oxides and ceramics that will not react with the flame. Heat is provided by an oxy-fuel gas flame, and the material is fed in as a wire or powder. Thicknesses of 50 µm or more can be reached, but the coatings are more porous than those obtained using the detonation gun or plasma spray techniques.

2.3. Sputtering

In sputtering, which is another form of PVD, the target, or source, is excited under vacuum into the gas phase using momentum transfer from the impact of high-energy ions from an ion gun. The sputtered source material is directed onto the substrate to form the coating.

2.4. Cladding

Cladding is perhaps the oldest form of coating. This consists of simply covering a substrate with a protective surface layer. This is generally done mechanically using roll bonding, coextrusion, or explosive cladding.

3

Thermal-barrier coatings

Thermal-barrier coatings (TBCs) are ceramic coatings which are applied to components for the purpose of insulation rather than oxidation protection. The use of an insulating coating coupled with internal air cooling of the component, lowers the surface temperature of the component with a corresponding decrease in the creep and oxidation rates of the component. The use of TBCs has resulted in a significant improvement in the efficiency of gas turbines.

Coating degradation

1

Oxidation-resistant coatings

Additional factors arise with coatings; since they are relatively thin, they contain a finite reservoir of the scale-forming elements (Al, Cr, Si), and interdiffusion with the substrate can both deplete the scale-forming element and introduce other elements into the coating. Additional mechanical affects also arise, which can lead to deformation of the coating. Mechanical effects are also critical to the durability of TBCs.

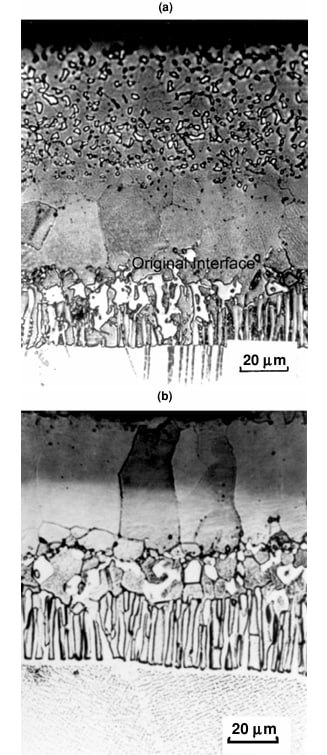

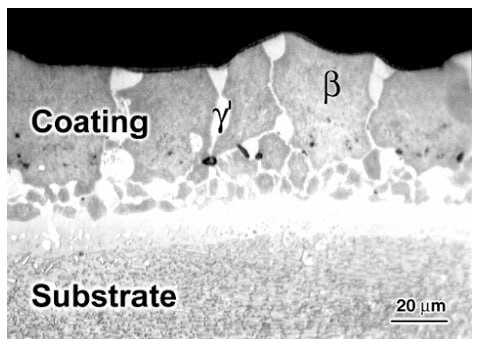

1.1. Degradation of diffusion and overlay coatings

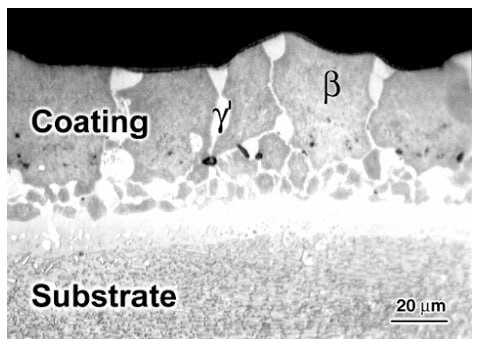

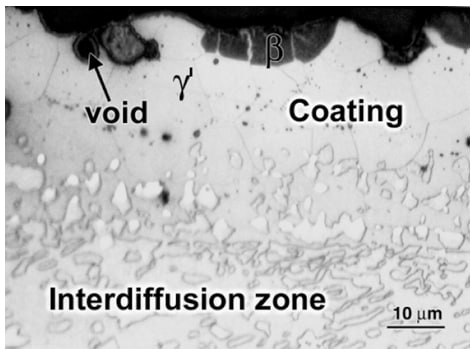

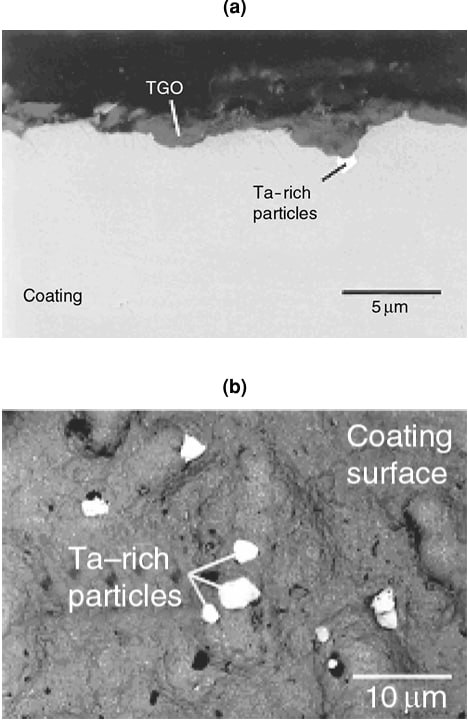

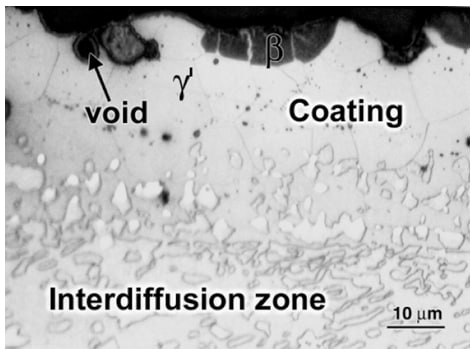

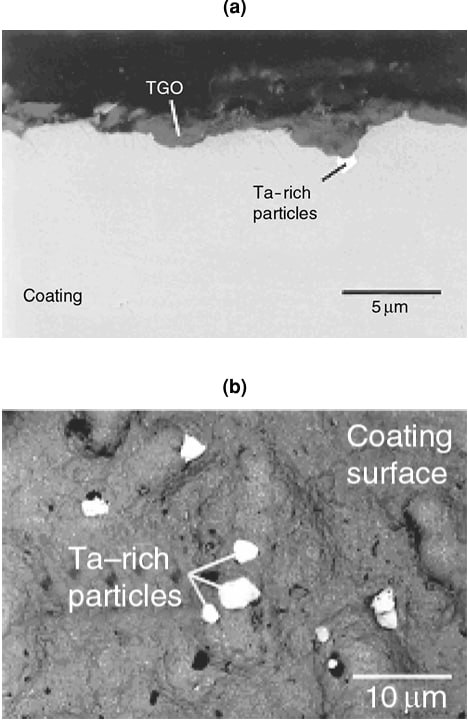

The microstructure of a platinum modified aluminide coating after 20h of exposure at 1200°C is shown in Figure 1. The initial columnar structure of the β-phase is evident. The depletion of Al has resulted in the nucleation of γ' at the β grain boundaries (light areas). Figure 2 shows the same type of coating after oxidation at 1200°C for 200 h. The coating had been converted almost completely to γ', as the result of Al depletion. Continued exposure would result in the γ' transforming to γ. Figure 3 shows the presence of Ta-rich phases, which have formed near the coating–scale interface as the result of Ta diffusing up from the superalloy substrate during high-temperature exposure.

Figure 1: Microstructure of a platinum modified aluminide coating after 20h of exposure at 1200°C showing the columnar β-phase structure and initial γ' formation at grain boundaries.

Figure 2: The same coating after 200h at 1200°C showing almost complete transformation to γ' phase due to aluminum depletion.

Figure 3: Formation of Ta-rich phases near the coating-scale interface resulting from tantalum diffusion from the substrate during high-temperature exposure.

1.2. Coatings on titanium aluminides

Coatings of TiAl3 have been formed by pack cementation on α2-Ti3Al, and γ-TiAl. These coatings form continuous alumina scales but TiAl3 is an extremely brittle compound and tends to crack, particularly for thicker coatings. It is also likely that the presence of a layer of TiAl3 on the surface of α2 or γ will be as embrittling as a high-temperature oxidation exposure.

1.3. Thermal-barrier coatings

The presence of the TBC can affect the performance of the bond coat and thermal stresses in the TBC can contribute to spalling of the TGO. This is important in that first-time spallation removes the TBC, which cannot reform, as is the case with a simple oxidation resistant coating. There are a number of degradation modes, which can limit the life of a TBC and these must be understood in order to make lifetime predictions for existing systems and to provide the basis for the development of improved TBC systems.

Summary

Protective coatings are essential for extending the service life of components in high-temperature oxidizing and corrosive environments. The selection of an appropriate coating system depends on the specific application requirements, including temperature, environment, mechanical loading, and component geometry. Diffusion coatings provide excellent adhesion but limited compositional flexibility, while overlay coatings offer greater compositional control but may have adhesion challenges. Thermal barrier coatings provide thermal insulation in addition to some oxidation protection. All coating systems are subject to degradation mechanisms that must be understood to predict component lifetimes and develop improved coating technologies.